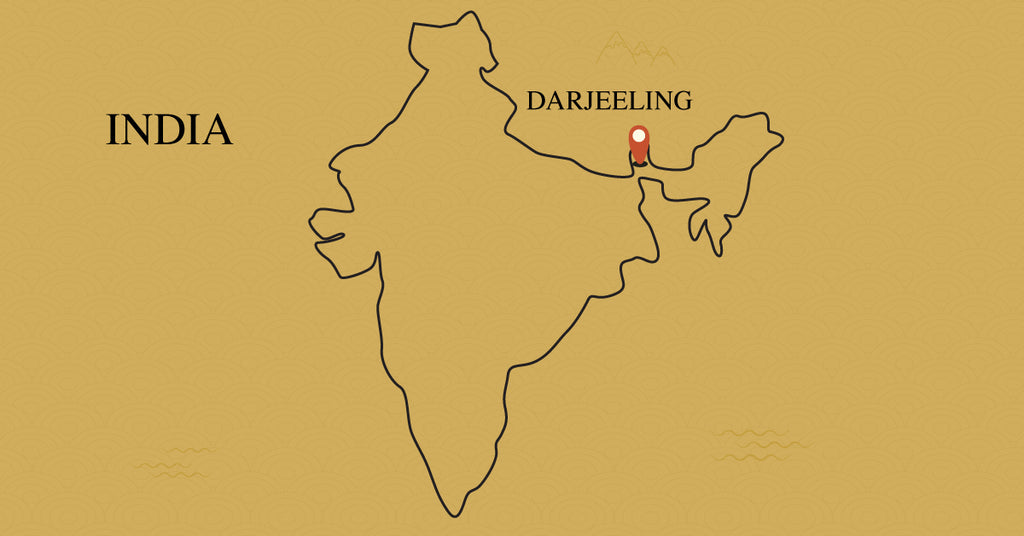

The northeastern region of Darjeeling on the border of Nepal and Bhutan is famous for three seasons of tea: the spring’s First Flush, the early summer’s Second Flush and the late summer and fall’s Autumnal teas. Though they grow more subdued the farther they get from spring, all three seasonal teas have a charming rounder quality, a depth and gentleness that rivals Chinese black teas. The First Flushes in particular have lively floral and fruit aromas to rival oolongs. Darjeelings have more tropical flavors like pineapple and guava, but more bite than Chinese black teas due to their more hastened oxidization. Read on to learn more about the Darjeeling tea region and the teas that are produced there.

Darjeeling Tea Region History

Although Darjeeling tea is quite popular, Darjeeling has produced teas only since the 1830s, and there are only 87 registered Darjeeling estates in the world. In their quest to grow tea in India, the British discovered that the native Chinese tea bush, Camellia sinensis var. Sinensis, flourished there. In what remains one of the highest-altitude-tea-growing regions in the world, in the cool air and hardscrabble soil of the Himalayan foothills, the tea leaves grow slowly, taking on lovely variegated flavors. Though British plantations marketed their product as the Champagne of teas, what they churned out was heavy, dark, and brisk, almost begging for the softening effects of milk and sugar. Many of our older customers still pine for this traditional Darjeeling flavor.

In 1947, independence brought an end to the Raj, and British influence in the region waned. Great Britain began importing the bulk of its teas from Africa. In the late 1960s, in a search for new teas to capture a fresh audience, Bernd Wulf, the father of our current, primary importer, worked with an Indian tea dealer named Ranabir Sen. The 2 experimented with lightening the teas to let the leaves’ flavorful qualities come through.

First, they made sure the harvesters gathered only the most flavorful parts of the plant. Following the Chinese example, the harvesters plucked only young leafsets of 2 leaves and a bud. Then they lengthened the withering time to build up the teas’ extraordinary aromas and give them a lighter, almost greenish cast. To fight off the cold and damp weather, tea makers in Darjeeling wither their leaves in heated troughs. Wulf and Sen found that if they left the leaves in the troughs long after the leaves had gone limp, in what’s now called a “hard wither,” the teas took on remarkably strong aromas similar to those of oolongs. The tea’s flavors also became more complex. Hard withering kept many of the leaves green by deactivating a percentage of the enzyme that would otherwise cause the leaves to oxidize. The hard withering affects different cultivars to varying degrees; since most gardens use a variety of clones, many good Darjeelings have a beautiful mixture of black and green leaves.

Wulf and Sen also carefully adjusted the rolling process, making sure the teas did not get overheated and lose their flavors from excess pressure or friction. They monitored the oxidation and shortened the firing time significantly, to show off the improvements in flavor rather than cover them with heavy firing. Thanks to their efforts, we can enjoy a range of aromatic, flavorful Darjeeling teas.

First Flush Darjeeling Teas

Like Chinese Qing Ming teas and Japanese Senchas, First Flush Darjeelings consist of the first leaves and buds to flush in early spring. In fact, the weather is starting to warm up in Darjeeling right now and First Flush is slowly starting. Spring teas are so prized because they have a bigger share of what makes tea so delicious. During the winter the plants go dormant, storing sugars and other compounds in their roots. As the weather warms, the plants send out those sugars and other tasty compounds to the tips of the plants to fuel new leaf growth. In the cool spring weather, the leaves grow slowly, making their flavor compounds even more concentrated and complex.

To help bring out these more nuanced flavors, tea makers oxidize First Flush teas for less time than they do teas harvested later in the season. They stop the First Flush after what they call the “first nose,” a particular scent that emerges about 2 hours after the leaves are rolled. First Flush teas are therefore quite green, both because of their shorter oxidation and because of hard withering.

Over the last decade, competition over the earliest First Flush teas has gotten quite intense. Few people in India take notice of them, since the national beverage is chai from CTC (cut-tear-curl) teas. Nonetheless, tea drinkers in Germany and, increasingly, Japan and the United States are quite fond of them. Japanese businessmen increasingly offer Darjeeling First Flush teas to colleagues as tokens of respect.

Second Flush Darjeeling Teas

Classic Second Flush Darjeeling teas have a mellow, more subdued, cooked stone fruit character. Second Flush leaves emerge a few weeks after the First Flush passes. The First Flush lasts for 3 to 4 weeks in early spring, ending when the plant does not make any leaves as it regenerates energy. This in-between period is known as Banji. Then in late May or early June, the plant starts to grow again. Though bigger and tougher than the tender First Flush leaves, Second Flush leaves are still full of flavor.

Darjeeling Tea Makers adjust their production methods from First Flush to Second Flush to accommodate the larger, older leaves. Darjeeling tea makers harness the plants’ self-defenses by allowing their natural predators, leaf mites, to feast on the leaves right before harvesting them. During the feasting, the leaves repel the predators by releasing defense in the form of aromatic compounds. When the tea is made, the compounds create the lovely fruity flavors in our mouths.

As with First Flush teas, the tea makers hard-wither the leaves after harvesting to concentrates their aromas. After rolling the leaves, they oxidize them 30% longer. First Flush teas oxidize until the first nose — a certain distinctive, strong aroma that emerges after about 2 hours. Second Flush teas oxidize for about another 40 minutes to an hour. The first nose emerges, at which point the tea maker fires the leaves in an oven. The firing lasts just under half and hour, to add gentle roasted flavors.

If you’re interested in trying teas from the Darjeeling tea region, we suggest you sip on our Lingia First Flush or Singbulli Second Flush or Singell Second Flush.

Want to learn more about the world of tea? Read a few of our favorite posts below and expand your tea expertise:

3 comments

Nancy

What is the strongest of the Black teas? I love tea but it doesn’t give me enough umph in the morning.

Thank you,

Nancy

What is the strongest of the Black teas? I love tea but it doesn’t give me enough umph in the morning.

Thank you,

Nancy

Gary Patterson

Single estate first flush teas like Lingia are wonderful. We drink them at least three or four times each week. Kudos to Harney and Sons for making these treasures readily available.

Single estate first flush teas like Lingia are wonderful. We drink them at least three or four times each week. Kudos to Harney and Sons for making these treasures readily available.

Thomas M. Huber

Thank you for this information.

Thank you for this information.